By Sharon Begley

NEW YORK (Reuters) - Powerful earthquakes thousands of miles away can

trigger swarms of minor quakes near wastewater-injection wells like those used

in oil and gas recovery, scientists reported on Thursday, sometimes followed

months later by quakes big enough to destroy buildings.

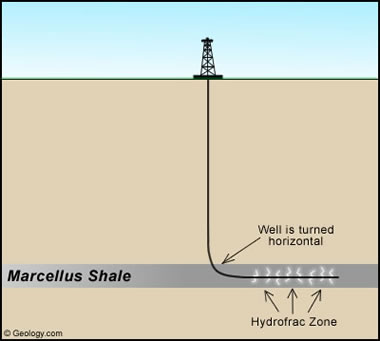

The discovery, published in the journal Science by one of the world's

leading seismology labs, threatens to make hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking,"

which involves injecting fluid deep underground, even more controversial.

It comes as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency conducts a study of

the effects of fracking, particularly the disposal of wastewater, which could

form the basis of new regulations on oil and gas drilling.

Geologists have known for 50 years that injecting fluid underground can

increase pressure on seismic faults and make them more likely to slip. The

result is an "induced" quake.

A recent surge in U.S. oil and gas production - much of it using vast

amounts of water to crack open rocks and release natural gas, as in fracking, or

to bring up oil and gas from standard wells - has been linked to an increase in

small to moderate induced earthquakes in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Ohio, Texas and

Colorado.

Now seismologists at Columbia University say they have identified three

quakes - in Oklahoma, Colorado and Texas - that were triggered at injection-well

sites by major earthquakes a long distance away.

"The fluids (in wastewater injection wells) are driving the faults to their

tipping point," said Nicholas van der Elst of Columbia's Lamont-Doherty Earth

Observatory in Palisades, New York, who led the study. It was funded by the

National Science Foundation and the U.S. Geological Survey.

Fracking opponents' main concern is that it will release toxic chemicals

into water supplies, said John Armstrong, a spokesman for New Yorkers Against

Fracking, an advocacy group.

But "when you tell people the process is linked to earthquakes, the

reaction is, 'what? They're doing something that can cause earthquakes?' This

really should be a stark warning," he said.

Fracking proponents reacted cautiously to the study.

"More fact-based research ... aimed at further reducing the very rare

occurrence of seismicity associated with underground injection wells is

welcomed, and will certainly help enable more responsible natural gas

development," said Kathryn Klaber, chief executive of the Marcellus Shale

Coalition.

'DYNAMIC TRIGGERING'

Quakes with a magnitude of 2 or lower, which can hardly be felt, are

routinely produced in fracking, said geologist William Ellsworth of the U.S.

Geological Survey, an expert on human-induced earthquakes who was not involved

in the study.

The largest fracking-induced earthquake "was magnitude 3.6, which is too

small to pose a serious risk," he wrote in Science.

But van der Elst and colleagues found evidence that injection wells can set

the stage for more dangerous quakes. Because pressure from wastewater wells

stresses nearby faults, if seismic waves speeding across Earth's surface hit the

fault it can rupture and, months later, produce an earthquake stronger than

magnitude 5.

What seems to happen is that wastewater injection leaves local faults

"critically loaded," or on the verge of rupture. Even weak seismic waves from

faraway quakes are therefore enough to set off a swarm of small quakes in a

process called "dynamic triggering."

"I have observed remote triggering in Oklahoma," said seismologist Austin

Holland of the Oklahoma Geological Survey, who was not involved in the study.

"This has occurred in areas where no injections are going on, but it is more

likely to occur in injection areas."

Once these triggered quakes stop, the danger is not necessarily over. The

swarm of quakes, said Heather Savage of Lamont-Doherty and a co-author of the

study, "could indicate that faults are becoming critically stressed and might

soon host a larger earthquake."

For instance, seismic waves from an 8.8 quake in Maule, Chile, in February

2010 rippled across the planet and triggered a 4.1 quake in Prague, Oklahoma -

site of the Wilzetta oil field - some 16 hours later.

That was followed by months of smaller tremors in Oklahoma, and then the

largest quake yet associated with wastewater injection, a 5.7 temblor in Prague

on November 6, 2011.

That quake destroyed 14 homes, buckled a highway and injured two

people.

The Prague quake is "not only one of the largest earthquakes to be

associated with wastewater disposal, but also one of the largest linked to a

remote triggering event," said van der Elst.

The Chile quake also caused a swarm of small temblors in Trinidad,

Colorado, near wells where wastewater used to extract methane from coal beds had

been injected.

On August 22, 2011, a magnitude 5.3 quake hit Trinidad, damaging dozens of

buildings.

The 9.1 earthquake in Japan in March 2011, which caused a devastating

tsunami, triggered a swarm of small quakes in Snyder, Texas - site of the

Cogdell oil field. That autumn, Snyder experienced a 4.5 quake.

The presence of injection wells does not mean an area is doomed to have a

swarm of earthquakes as a result of seismic activity half a world away, and a

swarm of induced quakes does not necessarily portend a big one.

Guy, Arkansas; Jones, Oklahoma; and Youngstown, Ohio, have all experienced

moderate induced quakes due to fluid injection from oil or gas drilling. But

none has had a quake triggered by a distant temblor.

Long-distance triggering is most likely where wastewater wells have been

operating for decades and where there is little history of earthquake activity,

the researchers write.

"The important thing now is to establish how common this is," said

Oklahoma's Holland, referring to remotely triggered quakes. "We don't have a

good answer to that question yet."

Before the advent of injection wells, triggered earthquakes were a purely

natural phenomenon. A 7.3 quake in California's Mojave Desert in 1992 set off a

series of tiny quakes north of Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, for

instance.

Now, according to the Science paper, triggered quakes can occur where human

activity has weakened faults.

Current federal and state regulations for wastewater disposal wells focus

on protecting drinking water sources from contamination, not on earthquake

hazards.

(Reporting by Sharon Begley; Additional reporting by Edward McAllister;

Editing by Michele Gershberg and Xavier Briand)